--- Five men, full of determination for material success according to the American dream and endowed with strong wills to pursue their goals, were thrown together in South Texas by circumstances in the Reconstruction Period (after the Civil War) and sought to accomplish their aims by uniting into a single business.

"Coleman, Mathis and Fulton, Dealers and Shippers of Live Stock," declared the letterhead on the stationery of the partnership that was formed in 1871 with headquarters in Rockport.

The partners and the proportion of property owned, were: Youngs Coleman and Thomas Matthew Coleman, one-third; John M. Mathis and Thomas Henry Mathis, one-third; and George Fulton, one-third.

The primary reason for the founding of the Coleman, Mathis and Fulton partnership was to raise cattle on their own property, to provide a market for livestock from local, smaller ranches, and to lease pasturage for other persons' animals. A favored location was obtained for this enterprise. Based at a natural harbor on Aransas Bay and serving as agent for a large ocean transport company Colman, Mathis, and Fulton handled nearly all the shipments that were produced west of the Guadalupe River.

115,000 Acres in Two Counties

Soon after organization in 1871, Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton stretched its range to cover 115,000 acres in San Patricio and Refugio (later Aransas) Counties. Natural mile-long fence on the west from Nueces Bay to Chiltipin Creek enclosed approximately 200,000 acres of land including Live Oak Peninsula, where the towns of Rockport, Fulton, and Ingleside were situated. The north, east, and south limits of the ranch were natural boundaries -Chiltipin Creek, Copano Bay, and Corpus Christi Bay - except for a fence eight miles long from Puerto Bay to Corpus Christi Bay cutting off the point of the Peninsula and creating a 115,000-acre pasture.

During the 1870s the ranch continued to acquire land by spreading out over San Patricio County and western Aransas County. Plots of ground measuring from a quarter section to several thousands of acres in each transaction were bought at prices ranging from $.35 to $2.45 an acre.

With the acquisition of property their company purchased cattle to place on it. Dogged by hard times, the ranchers' difficulties were particularly increased by the harsh winter of 1872-1873, which took a toll of the livestock, and by the financial depression of 1873, which started in the Northeast but reached its dark hand of economic gloom into Texas. Outlets to the North were dried up as banks closed, and money was difficult to come by in the midwestern cattle-buying centers. Texas ranchers were forced to sell more and more of their livestock to relieve the strain on dry pasture and to gain revenue. Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton bought many small herds and with the transactions went the brands. . .

In 1 Year, 264 Brands Bought

In the year 1875, alone the Coleman, Mathis and Fulton firm purchased 264 brands with marks from neighboring ranches, added a T on each animal's jaw to indicate the new owner, then turned the livestock onto their range. Calves yet unbranded received the main brand of the firm, CMF (connected), which was registered in the counties in which the company operated.

As livestock matured and became marketable, they were sold to packeries or to neighboring ranchers for a northern drive, or sent via ship to New Orleans or Havana (Cuba). . .

Colman, Mathis and Fulton contracted with the Morgan Line to transport its cattle during the 1870s. From October, 1872, to July, 1878 when the Aransas Pass inlet became too shallow for steamships, a total of 104,600 beeves, cows, calves, and yearlings were billed to New Orleans from Rockport. This number constituted about one-third of the firm's entire shipments, the balance sent from Indianola, principally to Havana. . .

Soon after the partnership was formed, it began upbreeding the herd. Fulton had resided in Covington Kentucky, for several years and in 1875 he corresponded with a Kentucky friend about purebred bulls to be used in Texas. The company's records do not mention when blooded stock was first introduced, but at the time of the dissolution in 1879, several dozen full-blooded Durams were on hand...

Headquarters of the sprawling Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton ranch were in Rockport, but the operational center for normal day-to-day activities was a place know as Rincon Ranch, west of Live Oak Peninsula across Puerto Bay. Other ranches named after persons who once owned the land or by natural features were the Brasada, Big Pasture, Stockley, Henry Bend, Cruz Lake, Mesquite, Pistola, Mud Flats, Consado, Puentez, Doyle Water Hole, Gollege, and Indianola Prairie.

IN the late 1870s George D. Whitney was foreman, and from the Rincon he commanded a host of employes who did the riding, cooking, fencing, milking, and other chores necessary on a cattle spread. Wages received by the foreman in 1879 were $88.33 a month, while $15 seemed to be the prevailing rate for those engaged in more routine tasks of little responsibility. . .

Cordiality Diminished in 1870s

In the latter 1870s the five partners were not as cordial in their relationship as they were when the business began. . . The uncordial atmosphere in the partnership resulted in its dissolution on August 7 1879. . .

In eight years the firm of Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton became a big business in South Texas as evidenced by the estimated value placed on all of the horse stock, cattle stock, and real and personal property. When the inventory was completed and the books closed on April 30, 1879, the debit and credit columns balanced at a little over one million dollars.

The five partners divided the property on an equitable basis. On August 7, 1879, they decided that Thomas M. Coleman m and George W. Fulton were to gain possession of the main range in San Patricio and Aransas Counties, while Thomas H. Mathis and John M. Mathis were to be given land in the areas more remote from Rockport. The new partnership of Coleman and Fulton, in which Thomas M. Coleman had an undivided three-eights' interest, Youngs Coleman one-eight, and George W. Fulton four-eights, received 16767,636 acres in San Patricio and Aransas Counties on the main range. This area contained the huge continuous block of land from Corpus Christi Bay on the south, Nueces Bay and a fence on the west, Chiltipin Creek on the north, and Copano and Puerto Bays on the east.

The Rockport dock with the land on which it stood including the real and personal property connected with it, went to Coleman and Fulton, as did 3,700 acres in Aransas County and 2,500 acres in San Patricio County not connected with the main pasture. Coleman and Fulton received also 6,081 acres in Live Oak County, for a total of 178,917 acres awarded to the new partnership.

The agreement of dissolution ended eight years of united effort to build an empire of land and cattle in South Texas. During that time the cattle kingdom grew, the packing-house era reached its peak and started to wane, barbed wire was invented and effectively used to enclose vast ranges, upbreeding of livestock became a practice rather than a dream, and other innovations occurred to change the lives of those in rural communities.

Windmills, Bared Wire, Purebreds

Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton are credited with the pseudo honor of being the first to introduce windmills, barbed wire, purebred cattle, and the telephone to South Texas. In these ways and others, post-Civil war Texas was dominated by change. Large ranches were carved from the public domain or from unoccupied territory, and what can be called the "Cattle-Baron Era" was ushered in. . .

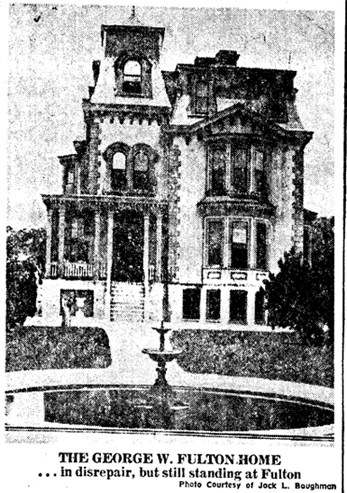

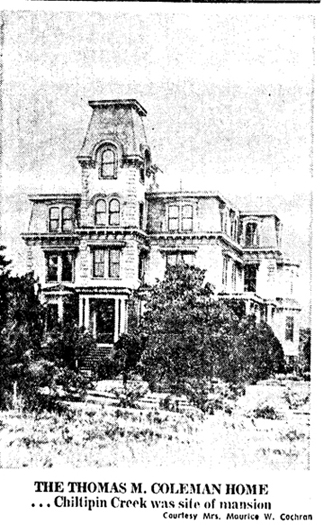

Two of the finest homes built on the South Texas during this era were constructed by George E. Fulton in Fulton and by Thomas M. Coleman on his Chiltipin Creek ranch, approximately 30 miles west of Rockport.

Fulton, a civil engineer by training and occupation before he turned to livestock raising, is said to have designed the plans for his four-story dwelling situated near the water's edge on Aransas Bay between Fulton an Rockport Beginning in 1872 work on the Fulton dwelling continued for four years before the family moved in. . .

Shipped from New Orleans were doors, sashes, shutters, Venetian blinds, stairways, and door trimmings of black walnut, as well as window glass, ornamental gateposts, an screens . . . Plumbing supplies were obtained in New York. The initial order called for French tubs, a 50-gallon copper boiler for hot water, French closet bowl, 14-inch marble basins, and black walnut stands . . A dumb waiter ordered from New York allowed food cooked in the basement kitchen to be served in the dining room in minimal time and with little effort. New furniture for the house was purchased in Cincinnati. . .

Orders Placed the Country Over

Expensive carpeting and draperies were purchased in New York; a custom-made silver tea-service set and silver table utensils, complete with a silver bell for signaling the servants, were ordered from a New York sliver smith; new bedding supplies were sent for, crystal chandeliers were designed and blown just for the occasion in New York; specially made doorknobs came from Philadelphia; lawn equipment and plants for landscaping were brought in from New Orleans; house paint was shipped on Morgan steamers from Baltimore and New York - all with apparent disregard for cost. The result was a beautiful structure that still stands almost a century later with no sign of exterior disrepair, although vandals have marred the bedrooms and upstairs hallways. Fulton in his correspondence did not state the total expense for erecting and furnishing his mansion, but a local newspaper editor in 1891 estimated the cost to be $100,000.

A housewarming and reception was held for the Fultons in their new home after it was completed and everyone was shown through the rooms for a personal inspection. A spark of jealousy was kindled in the wife of one of the Fulton's business associates. On the way home after the reception Mrs. Thomas M. Coleman informed her husband that she liked the house; in fact, she liked it so well that she wanted one built just like it, only larger and more ornate.

Construction started immediately at the Coleman Ranch, on Chiltipin Creek, and by 1880 the home was finished. One informant says that the Colemans tallied up to $80,000 and then quit counting. Another account states that the total sum was $150,000.

Elaborate furnishings were brought in; landscaping for a l mile around the house was attended to by persons employed for that purpose alone; stables, hunting dogs, and pens were installed for the benefit of ranch occupants and guests; fountains and statues were placed in the gardens. All this extravagance of both mansions spoke of the carefree, reckless abandon that characterized the cattle-baron era in Texas.

The period of range and cattle empires did not end with the dissolution of Coleman, Mathis, and Fulton. Rather, a new and larger venture awaited those who retained possession of the ranch carved from the wilderness. During the next half century a big business enterprise, led by the remnants of this firm, sponsored the settlement of the area and was largely responsible for the economic development if the South Texas Plains.